This street, established in 1991 as part of the development of the Elliott Bay Marina at the southern foot of Magnolia Bluff, runs ⅖ of a mile west from 23rd Avenue W to just shy of the 30th Avenue W street end beach.

While the origin of its name may not be interesting, the story of its establishment is a bit more so:

- The marina itself began the permitting process in 1983, but lawsuits delayed its creation for nearly a decade. The Muckleshoot Indian Tribe and Suquamish Tribe sued to block its construction on the basis that “construction of the Marina would eliminate a portion of one of their usual and accustomed fishing areas in Elliott Bay and thus would interfere with their treaty right to fish at the Marina site.” Homeowners on the bluff above intervened on the side of the developers, as “the area has had numerous major landslides that have left several homes at the crest of the bluff at risk and have repeatedly caused breaks in a trunk sewer line located at the base of the bluff.… The Marina construction includes the placement of 500,000 cubic yards of fill at the toe of the bluff, which would stabilize the area.” Eventually, a settlement was reached, which “calls for ongoing fisheries-related expenses paid to the tribe, which will be funded by a percentage of the moorage income.… [the] ‘Indian Treaty Surcharge.’”

- I believe this was the last major fill operation within Seattle city limits. Such a development would be all but unthinkable today.

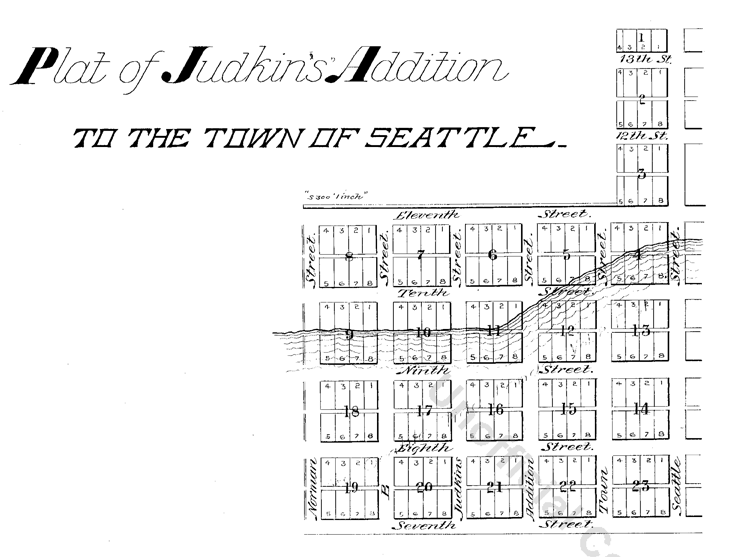

- The marina was built on tidelands where W Lee Street and Puget Avenue W were platted but never built. They were vacated and W Marina Place was established. When it came to naming the access road, the developers originally proposed W Marina Boulevard, contending that as the road fell between the W Oakes Street right-of-way and the former W Lee Street right-of-way, it wasn’t a violation of the city’s principle of maintaining street grid names as much as possible. This was initially rejected by the city, which preferred W Lee Street, but after further discussion, W Marina Place was settled on. An interesting point the developers made was that as W Lee Street had never physically existed in Magnolia, though it had been platted there, calling the access road W Lee Street could actually be confusing, as “people familiar with Seattle streets know that there is no W Lee Street on Magnolia. Rather, they know W Lee Street as being on Queen Anne Hill.” Still, though, I have to believe they were more interested in their own vanity — Marina Boulevard? — than any particular concern for folks’ ability to navigate.

- For some reason, the public street ends just feet from the 30th Avenue W street end beach. I’m not entirely sure why that is; I don’t think the marina is opposed to public access to the beach; otherwise, they wouldn’t be in favor of the Magnolia Trail project, which would connect W Marina Place to W Galer Street, 32nd Avenue W, and thence to Magnolia Village.

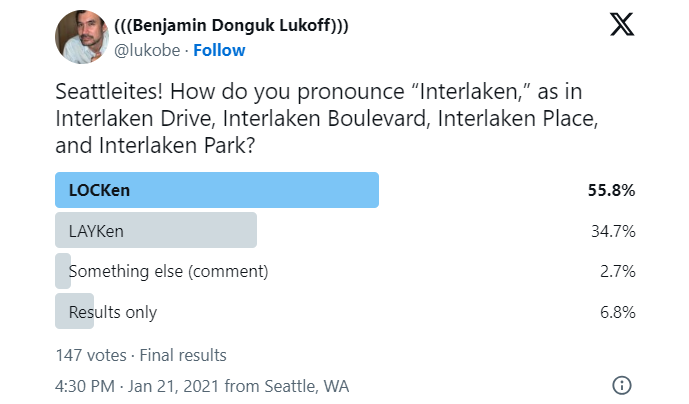

Born and raised in Seattle, Benjamin Donguk Lukoff had his interest in local history kindled at the age of six, when his father bought him settler granddaughter Sophie Frye Bass’s Pig-Tail Days in Old Seattle at the gift shop of the Museum of History and Industry. He studied English, Russian, and linguistics at the University of Washington, and went on to earn his master’s in English linguistics from University College London. His book of rephotography, Seattle Then and Now, was published in 2010. An updated version came out in 2015.