Like almost every other street in Fort Lawton (1900−2011), which became Discovery Park, Montana Circle was named after a state of the Union. Unlike almost every other street in Discovery Park, however, Montana Circle is a private road and in fact not part of the park at all. This is because the houses here, originally built for non-commissioned officers, were in use as military housing at the time the Army officially closed the fort. According to Monica Wooton of the Magnolia Historical Society, writing in the Queen Anne & Magnolia News, this meant that the property had to be sold at market rate instead of returned to the city as surplus, as most of the rest of the park had been. The city did manage to come up with $11 million to demolish some non-historic housing and restore the forest, but

Friends of Discovery Park could not get a partnership with government and other entities needed to purchase the Officer’s Row and NCO housing because of the cost mandated by the Privatization Act [while] the economic recession was taking hold.

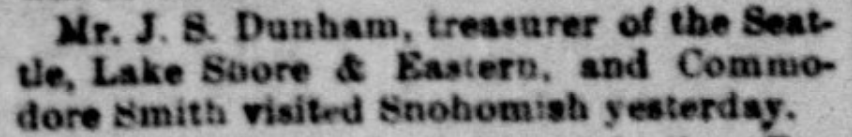

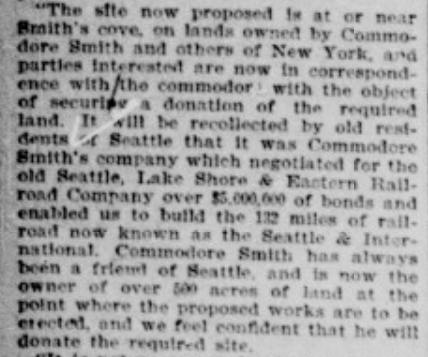

As the Seattle Daily Journal of Commerce reported in April 2016,

The 13 homes in Montana Circle at Fort Lawton all have sold in about three months, and prices on the ones that have closed average $484 a square foot. Prices ranged from $799,000 to $1,050,000.

This provided a nice profit for the real estate firm that bought Officer‘s Row and Montana Circle from the military for $9.5 million.

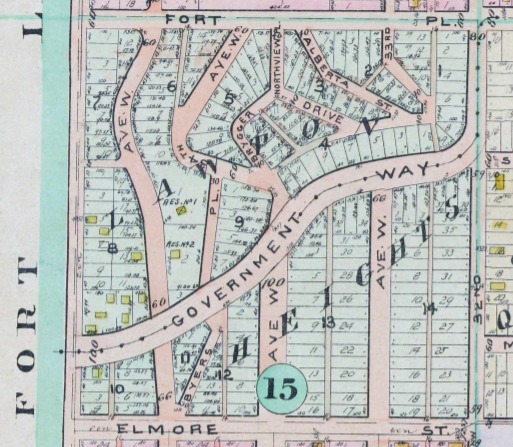

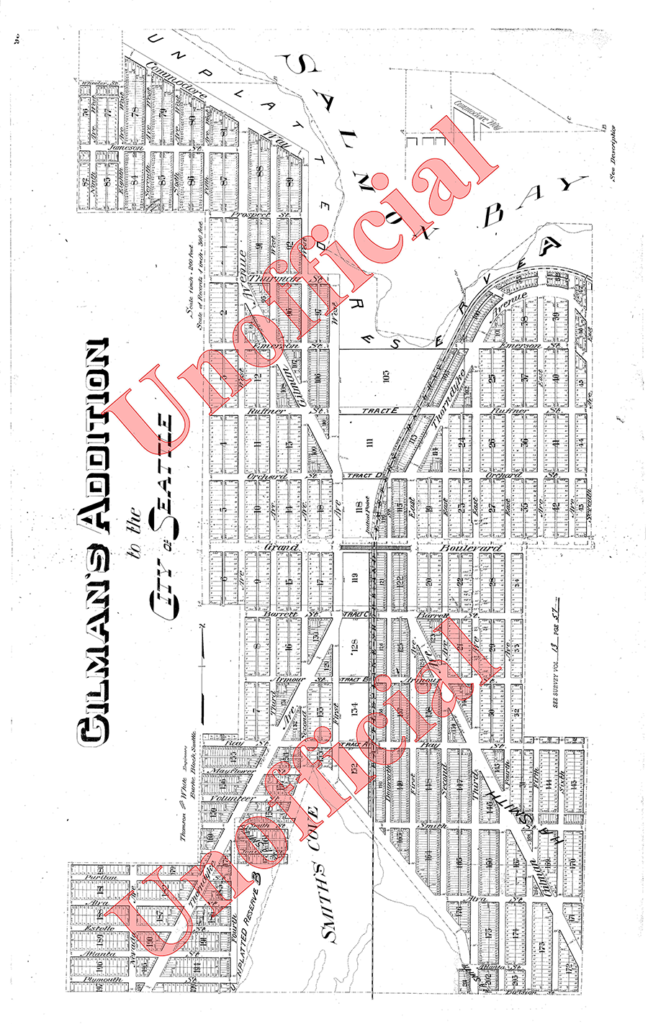

Montana Circle begins at Discovery Park Boulevard just east of Kansas Avenue and loops around to rejoin Discovery Park Boulevard around 100 feet to the east.

Born and raised in Seattle, Benjamin Donguk Lukoff had his interest in local history kindled at the age of six, when his father bought him settler granddaughter Sophie Frye Bass’s Pig-Tail Days in Old Seattle at the gift shop of the Museum of History and Industry. He studied English, Russian, and linguistics at the University of Washington, and went on to earn his master’s in English linguistics from University College London. His book of rephotography, Seattle Then and Now, was published in 2010. An updated version came out in 2015.