Contrary to what I wrote in “Elliott Way” just a placeholder name, it sounds like the new road connecting Western Avenue at Bell Street to Alaskan Way at Pike Street will in fact carry the official name of Elliott Way. To quote from a post on Mayor Bruce Harrell’s blog,

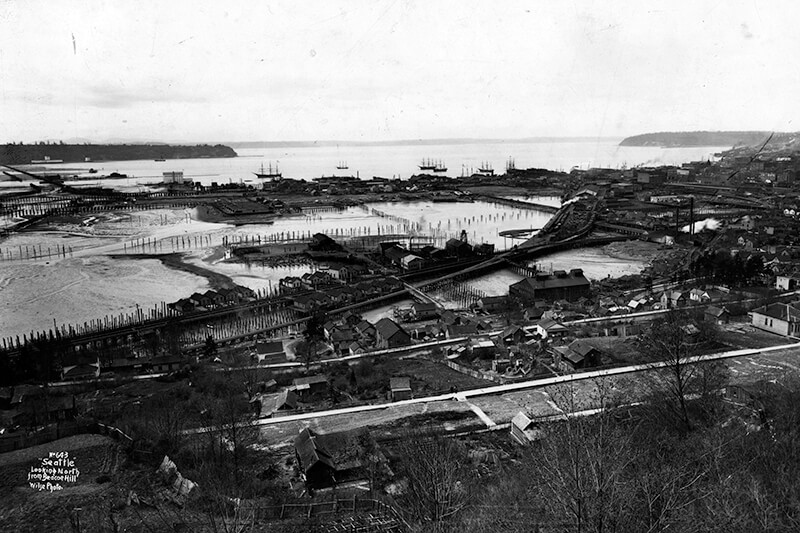

Mayor Bruce Harrell, City Council President Debora Juarez, and key waterfront leaders are proposing to establish an honorary name for Alaskan Way and Elliott Way, between S Dearborn St and Bell St. “Dzidzilalich” (pronounced: dzee-dzuh-lah-leech) means “Little Crossing Over Place” in the Coast Salish language Lushootseed. This honorary name would recognize the deep tribal history and culture on Seattle’s waterfront. The Dzidzilalich street name designation would be honorary; the legal name of “Alaskan Way” would not change nor would the official addresses on the street.

As I wrote in Rob Mattson Way, honorary renamings differ from official (re)namings in three important ways:

- They are done via resolution rather than ordinance

- They do not replace the original street name in official records and addresses

- They appear on brown, rather than green, signs

The Waterfront Seattle page on Dzidzilalich notes that “The Suquamish and Muckleshoot Tribal Councils provided guidance to the city of Seattle’s Mayor’s Office, the Office of the Waterfront and Civic Projects, and the Seattle Department of Transportation in the process of selecting Dzidzilalich as the honorary name for this roadway.”

I am glad to hear that this new street will carry a Lushootseed name. To the best of my knowledge only Duwamish Avenue S and Shilshole Avenue NW do so currently. To have a major downtown street with a name like this is long overdue.

I should also note that, if this is what the tribes want, I support the proposal — and though I have some issues with it, it is not my place to tell tribal members they deserve more. I have no idea what the negotiations looked like. That said, I do have some issues with the proposal.

First, “Elliott Way” remains an incredibly uncreative name for the new roadway. I said it before and I’ll say it again: “This is a [missed] opportunity to commemorate someone, or something, new, rather than Jared, George, Samuel, or Jesse Elliott (apparently no one is sure just which Elliott the bay is named after)!” There is nothing wrong with dead white men, but take a look at the tag cloud at the bottom of this post for proof that they are far overrepresented when it comes to Seattle street names.

Second, honorary names simply don’t carry the same heft as official ones. No one calls 19th Avenue between E Madison Street and E Union Street “Rev. Dr. S. McKinney Ave,” or 15th Avenue S between S Nevada Street and S Columbian Way “Alan Sugiyama Way.” But they do call Mary Gates Memorial Drive NE, E Barbara Bailey Way, Edgar Martinez Drive S, S Roberto Maestas Festival Street, etc., by those names… because they have no other choice.

I do like the idea of giving Alaskan Way an honorary name. It is far too long and important a street to officially rename without causing a lot of issues. The last time we did something like that was when Empire Way became Martin Luther King Jr. Way in the 1980s. I’m glad that happened, but think the process would be even more drawn out and controversial today. (However, if the street that runs along our waterfront carried the name of, say, a Confederate general, I’d be among the first to call for those signs to come down.) But why just this portion of Alaskan Way? To the best of my knowledge we’ve never given an existing street an honorary name for its entire length. Why not start here, from E Marginal Way S all the way to W Garfield Street?

In addition, one reason behind honorary namings is that existing addresses don’t need to be changed. But Elliott Way is new. There are no existing addresses. Why not, then, simply call it Dzidzilalich, and give Alaskan Way another honorary name? Or, why not give Alaskan Way the honorary name Dzidzilalich for its entire length, and give Elliott Way a different name that “elevate[s] Coast Salish tribal history and culture,” as the mayor’s blog puts it?

A few asides: I, personally, would prefer the spelling Dᶻidᶻəlalič, which uses Lushootseed orthography. (If Port Angeles can do it with their Klallam-language street signs, so can we!) And I notice that only the Suquamish and Muckleshoot tribes are mentioned as having been consulted. I wonder if representatives of the Duwamish Tribe were given a chance to weigh in as well. (My guess is they weren’t, as they are not federally recognized, while the Suquamish and Muckleshoot are, and oppose the efforts of the Duwamish to gain recongition. There is a long-standing controversy regarding the legitimacy of the Duwamish as the present-day representatives of Chief Seattle’s people. See The Politics of Paying Real Rent Duwamish in Seattle Met for an interesting take on the issue.)

Regardless of what happens, though, I am glad to see “Dzidzilalic” return to Seattle’s waterfront.

Where springs of clear water bubbled from the earth and the beach was sandy and free from rocks, there the Indians camped. Such a choice spot was Tzee-tzee-lal-litch, which Arthur Denny called Spring Street.

Sophie Frye Bass, “Pig-Tail Days in Old Seattle”

Born and raised in Seattle, Benjamin Donguk Lukoff had his interest in local history kindled at the age of six, when his father bought him settler granddaughter Sophie Frye Bass’s Pig-Tail Days in Old Seattle at the gift shop of the Museum of History and Industry. He studied English, Russian, and linguistics at the University of Washington, and went on to earn his master’s in English linguistics from University College London. His book of rephotography, Seattle Then and Now, was published in 2010. An updated version came out in 2015.