Fairview Avenue is one of a handful in the city that changes directional designations twice along a continuous stretch. The street begins in the south at Virginia Street as Fairview Avenue, but becomes Fairview Avenue N a block and a half to the north as it crosses Denny Way, and a mile north and east of that becomes Fairview Avenue E at E Galer Street and Eastlake Avenue E. It continues to E Roanoke Street, two miles from its origin, where it is interrupted by the Mallard Cove houseboat community. Picking up a block to the north, it then runs half a mile from E Hamlin Street to Fuhrman Avenue E and Eastlake Avenue E, just south of the University Bridge.

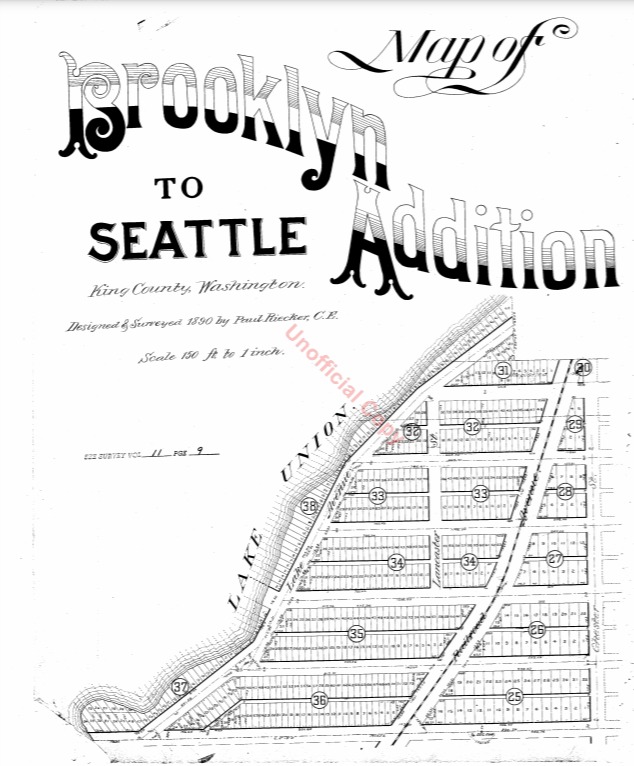

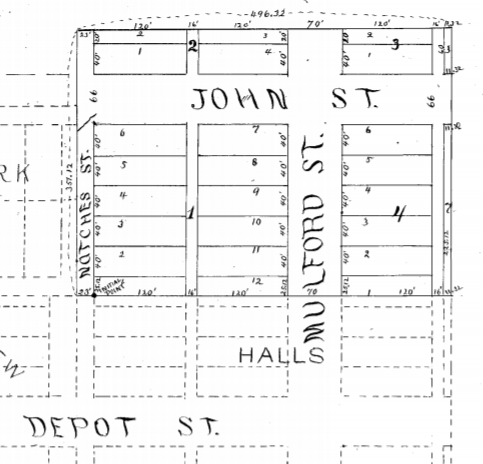

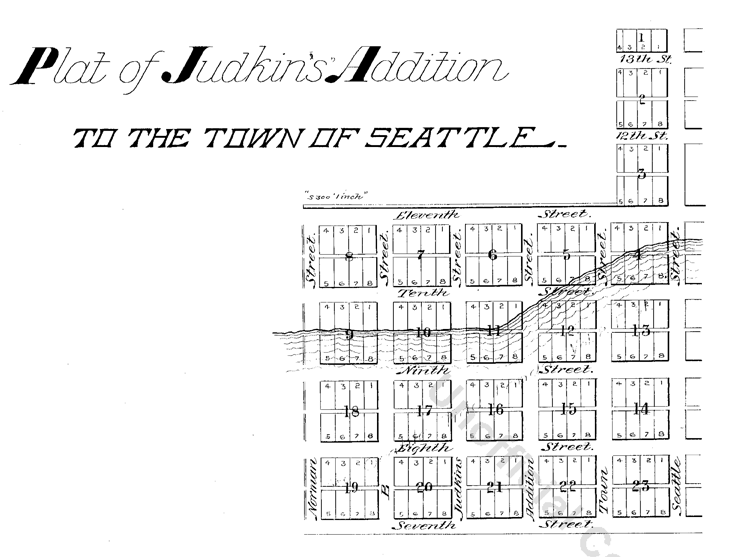

Originally Lake Street in Rezin and Margaret Pontius’s 1875 plat of the Fairview Homestead Association for the Benefit of Mechanics and Laborers, it received its current name during the Great Renaming of 1895. (Before 1875, it had been known as Prohibition Street.)

The Fairview Homestead Association, according to Paul Dorpat, was intended to “help working families stop paying rents and start investing in their own homes. Innovative installment payments made the lots affordable and many of the homes were built by those who lived in them.”

I assume Fairview took its name from the view of Lake Union and what is now Wallingford that is still barely visible today from what is now the Cascade neighborhood.

Born and raised in Seattle, Benjamin Donguk Lukoff had his interest in local history kindled at the age of six, when his father bought him settler granddaughter Sophie Frye Bass’s Pig-Tail Days in Old Seattle at the gift shop of the Museum of History and Industry. He studied English, Russian, and linguistics at the University of Washington, and went on to earn his master’s in English linguistics from University College London. His book of rephotography, Seattle Then and Now, was published in 2010. An updated version came out in 2015.