A new street connecting Elliott Avenue to Alaskan Way as part of the viaduct replacement project is currently under construction. When I first heard in 2016 that they were planning to call it Elliott Way, I thought it was a wasted opportunity. I wrote on my personal Facebook page “This is an opportunity to commemorate someone, or something, new, rather than Jared, George, Samuel, or Jesse Elliott (apparently no one is sure just which Elliott the bay is named after)!”

However, as it turns out, “Elliott Way” is just a placeholder name, just as “E Frontage Road S” was for what is now Colorado Avenue S at the south end of the new 99 tunnel.

On Boxing Day 2020 I finally wrote to the Seattle City Council and the Waterfront Seattle Program letting them know how I felt:

“The bay, and its namesake (most likely midshipman Samuel Elliott of the Wilkes expedition that explored Puget Sound in 1841) already has Elliott Avenue named in its honor. Elliott was, of course, a white man. I don’t know what percentage of Seattle streets are named for white men (although I would be fascinated to find out, and may undertake that as a project for my blog on Seattle street names), but I’m sure it’s very high.

“I urge you instead to take this opportunity to name this street something else. The Duwamish people, for example, have Duwamish Avenue S named for them (actually more likely for the river, as Elliott Avenue was named for the bay, not directly for the sailor), but it is an insignificant street 2/10 of a mile long hidden under the Spokane Street Viaduct and the Alaskan Freeway. Perhaps Duwamish Avenue would be a better choice, if the tribe approved? Or perhaps the street could honor a non-white person associated with the history of Seattle’s waterfront? Frank Jenkins, perhaps?”

I honestly didn’t expect to hear back from anyone, but to my surprise Marshall Foster, director of the Office of the Waterfront and Civic Projects, wrote me himself on January 5, saying:

We completely agree that the naming of this new street is an exciting opportunity. “Elliott Way” has simply been a placeholder until we are closer to its opening. The Coast Salish tribes are an incredibly important part of Seattle’s history and culture today. We have actually been thinking along similar lines about how this naming could help to elevate their presence here, and have been in discussions with our partners in the tribal community about ideas very similar to yours. We expect to have a proposal for public discussion later this year.

I have to say, I’m pretty happy about this.

Update as of January 11, 2022: I wrote Foster and his team over the weekend asking if there were any updates, and heard back today from Lauren Stensland:

We agree that this is a great opportunity and we continue to coordinate with the tribes and other partners on a proposed name. It is definitely high on our list for this year. We do not have any new updates at this time; we expect to have more to share in the next few months. Stay tuned and keep an eye on our website.

Update as of September 21, 2022: I recently wrote back to Stensland to check on the status of the street and its name, and she replied today that:

The elevated roadway is planned to open in early 2023. As for the roadway name, we are continuing to work toward this and will share updates as soon as we have them. Keep staying tuned!

Update as of February 2, 2023: I posted an article last month — “Dzidzilalich” to be honorary name for Elliott Way, Alaskan Way — noting that, in fact, the roadway will be known as Elliott Way… but will carry the honorary name “Dzidzilalich.” So it seems “Elliott Way,” after all, is unfortunately not just a placeholder name.

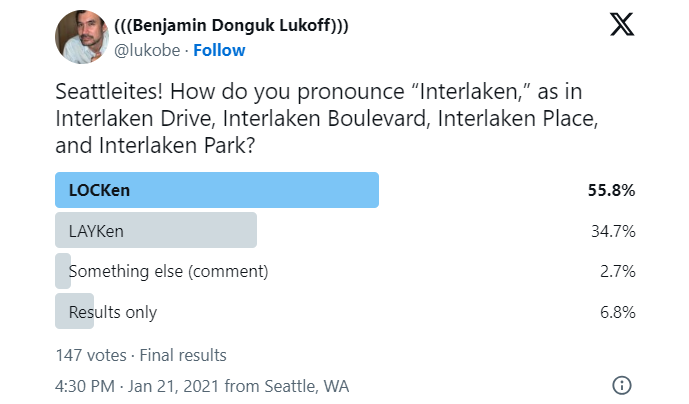

Born and raised in Seattle, Benjamin Donguk Lukoff had his interest in local history kindled at the age of six, when his father bought him settler granddaughter Sophie Frye Bass’s Pig-Tail Days in Old Seattle at the gift shop of the Museum of History and Industry. He studied English, Russian, and linguistics at the University of Washington, and went on to earn his master’s in English linguistics from University College London. His book of rephotography, Seattle Then and Now, was published in 2010. An updated version came out in 2015.