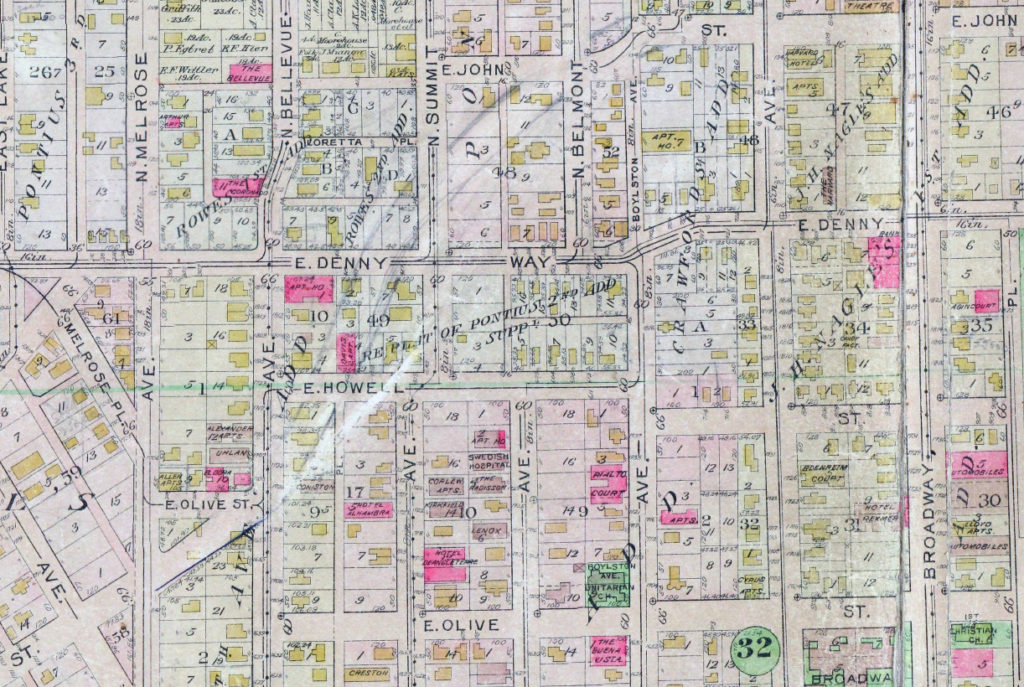

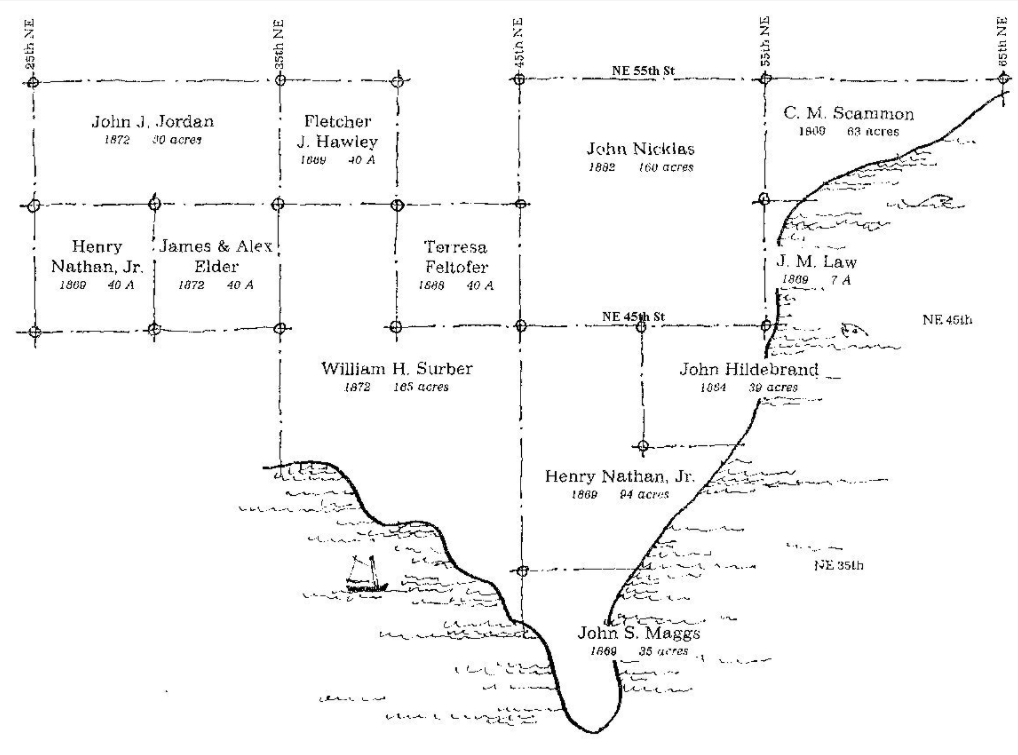

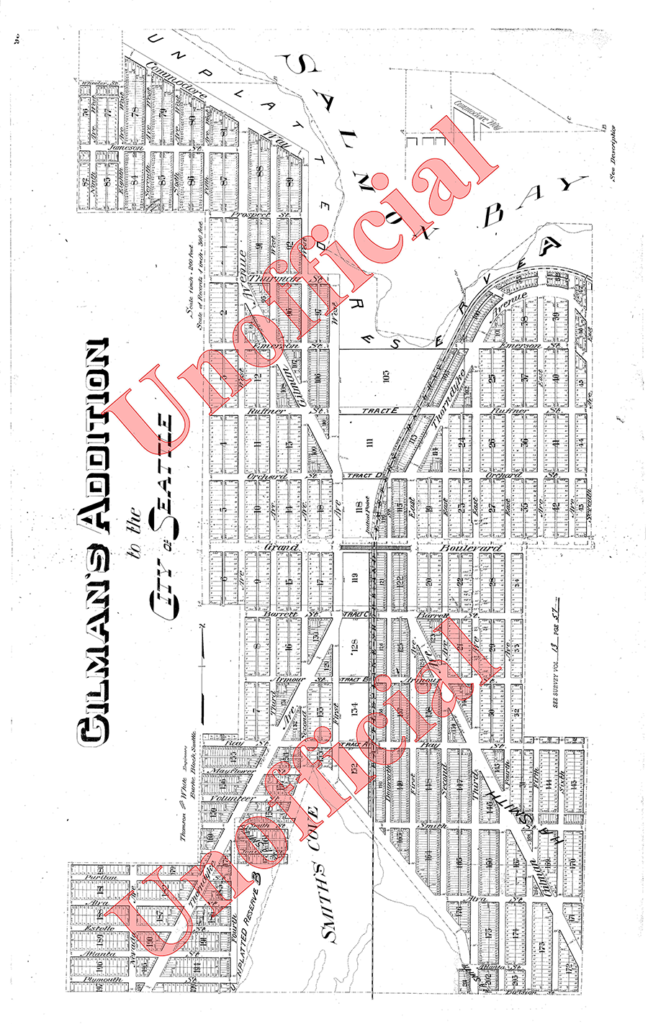

This street was named for Grace Chalmers Thorndike (, who married Daniel Hunt Gilman (Gilman Avenue W) in 1888. It was created in 1890 as part of Gilman’s Addition to the City of Seattle. The original plan was that Gilman and Thorndyke Avenues would intersect each other at Grand Boulevard (now W Dravus Street), but this was changed, as can be seen in the plat map below, likely in the knowledge that the tracks of the Seattle, Lake Shore and Eastern Railway would soon multiply and make that impractical.

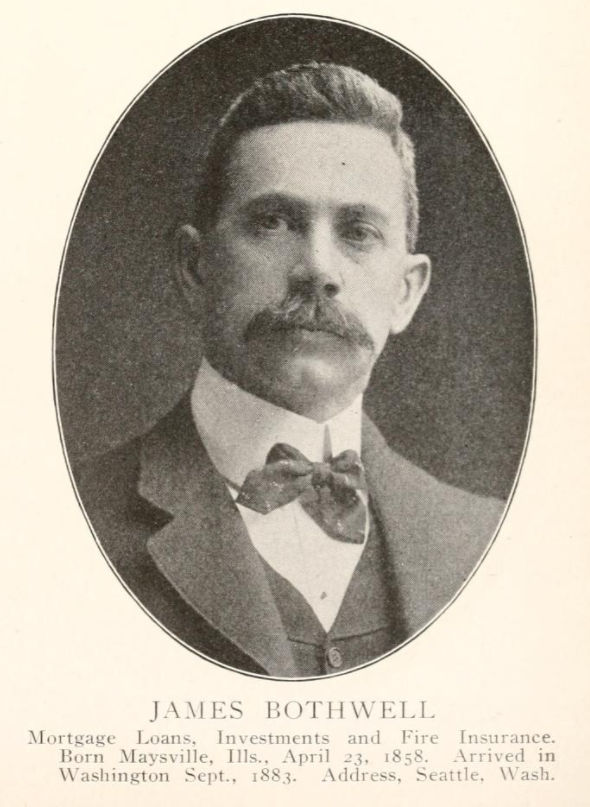

It’s not entirely clear why the street is named Thorndyke rather than Thorndike. There was an announcement of the Gilman–Thorndike wedding in the January 15, 1888, issue of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer that spelled the name with a y, but otherwise the family’s name routinely appears in the Seattle press with an i. Yet we see that Grace’s sister Minnie — wife of James Bothwell (W Bothwell Street) — spelled her name with a y (at any rate, that is what appears on her tombstone).

(It’s also worth noting that Grace’s sister Estella married Captain William Rankin Ballard, after which the Ballard neighborhood is named, and her sister Delia married Ballard’s business partner Captain John Ayres Hatfield. The Thorndikes’ father was himself a ship’s captain, one Ebenezer Augustus Thorndike.)

Today, Thorndyke Avenue W begins at W Galer Street, at the west end of the Magnolia Bridge, and goes just over a mile northwest to 20th Avenue W and W Barrett Street. It picks up again as a minor road on the other side of the BNSF Railway tracks, going about ⅕ of a mile northwest from 17th Avenue W and W Bertona Street to a dead end under the 15th/Emerson/Nickerson overpass at the south end of the Ballard Bridge.

Born and raised in Seattle, Benjamin Donguk Lukoff had his interest in local history kindled at the age of six, when his father bought him settler granddaughter Sophie Frye Bass’s Pig-Tail Days in Old Seattle at the gift shop of the Museum of History and Industry. He studied English, Russian, and linguistics at the University of Washington, and went on to earn his master’s in English linguistics from University College London. His book of rephotography, Seattle Then and Now, was published in 2010. An updated version came out in 2015.