It isn’t often that a vintage newspaper article explicitly states the reason behind a new street’s naming, but when it comes to Radford Drive, we’re in luck. On November 30, 1940, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported, under the headline ‘Work started at Sand Point Homes project’, that ground had been broken the day before on a project to house 150 enlisted men, plus their families, from the adjacent Sand Point Naval Air Station. (The project was said to cost $620,000, which is ¾ of the average price of a single home in Seattle today!) Rather amusingly, the air station’s commandant, Captain Ralph Wood, is quoted as saying “the days when the sailor was a bachelor and a derelict have long since passed” as justification for the need for military family housing. The article goes on to say that:

Street entrance to the area will be named Radford Drive in honor of Commander Arthur W. Radford, former commandant of the Sand Point base, who launched the expansion program which has resulted in its present growth.

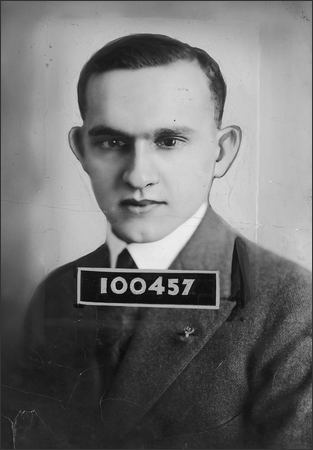

Arthur W. Radford (1896–1973), who had been appointed commandant in 1939, was promoted to captain in 1942 and to rear admiral in 1943. He became vice admiral in 1945, and was appointed by President Harry S. Truman as vice chief of naval operations in 1948. In 1949, he was made high commissioner of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands as well as commander-in-chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, and in 1953 he became President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s selection as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He retired from the Navy in 1957.

Today, the housing complex, redeveloped in 2001, is known as Radford Court, and is owned by the University of Washington, though some units are available to the public. Interestingly, the entrance to the neighborhood from NE 65th Street is signed Radford Drive NE and is on University-owned land, while the publicly owned street is legally NE Radford Drive, but not signed at all — and the addresses for the complex are on 65th Avenue NE (one of the city streets, the other being NE 64th Street, that connects directly to the property).*

* Yes, NE 65th Street and 65th Avenue NE intersect here. Because of how Seattle’s street naming system works, Windermere and Laurelhurst are the site of a number of similar intersections, including those for 60th, 59th, 57th, 55th, 54th, 50th, 47th, 45th, 43rd, 41st, and 40th.

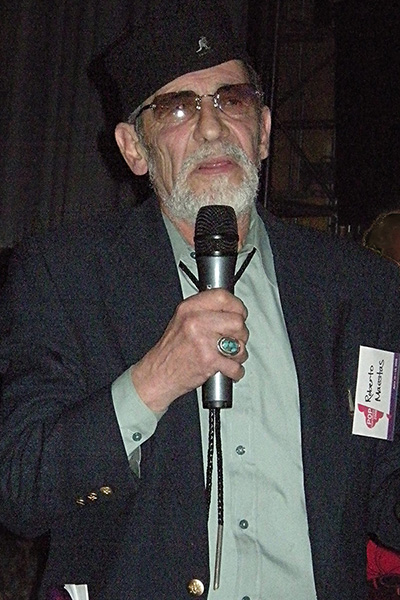

Born and raised in Seattle, Benjamin Donguk Lukoff had his interest in local history kindled at the age of six, when his father bought him settler granddaughter Sophie Frye Bass’s Pig-Tail Days in Old Seattle at the gift shop of the Museum of History and Industry. He studied English, Russian, and linguistics at the University of Washington, and went on to earn his master’s in English linguistics from University College London. His book of rephotography, Seattle Then and Now, was published in 2010. An updated version came out in 2015.